on

When the Internet Splits

What happens when the World Wide Web loses some strands.

This is an opinion piece, as much as it is news.

The internet in 20 seconds

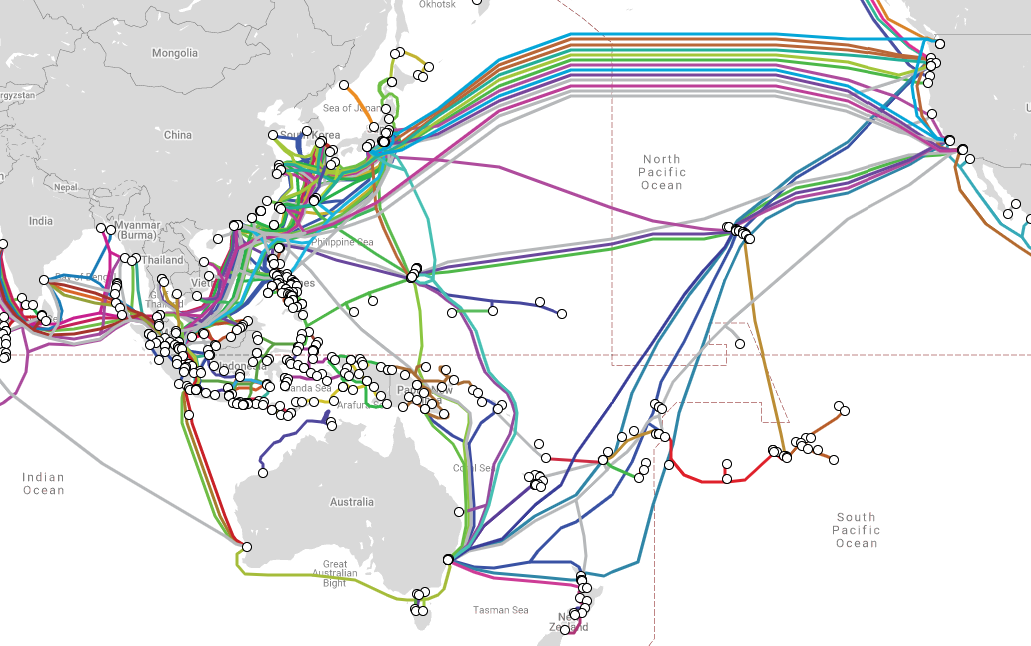

The Internet is a product of a collection of standards governing how autonomous systems talk to each other. Peering points connect multiple networks (such as your residential ISP, or Google’s network), these peering points are connected via long lengths of fibre optic cable, a vast majority of which is underwater (subsea cables).

The Internet’s power comes from how unified it is, it’s a single connection which enables you to reach an unfathomable amount of websites and services. It flourished because of how open it was, anyone with the technical knowledge could publish their opinions and creations for the ever-connected world to see.

How it’s falling apart

Decay has always been a familiar part of the internet, websites come and go, popularity flows like a wave and despite the efforts of archivists and online historians many beautiful and unseen creations fall by the wayside, drowning in the firehose of content.

But this recent decay is unnatural, a forced move by those who still don’t understand the complex agreements and shared standards that have created a nearly universal platform. It comes in the form of 2 attacks: Attacks on encryption and security and the freedom of information to flow.

These attacks provide a risk of destroying the unification that has been tended to by countless passionate engineers and enthusiasts, by forcing the standards that underpin the internet to be a political issue we risk losing the ability to have that unified platform.

Backdoors Are Just Someone Else’s Front Door: Encryption and Security

There have been a significant amount of political moves to ban or force backdoors into encryption, notably by the US and UK (there are also Australia’s metadata retention laws, which lay in a similar vein).

We’ve been lucky so far, in that the vocal community has denied these pushes in the US and UK so far. However, the US is currently pushing two anti-encryption bills: The EARN-IT act and LAED. The EARN IT act focuses on removing the protection that services such as YouTube have against those who post illegal content on the platform, such that if you don’t comply with mandatory backdoors you will be liable for the content.

It’s a nasty bill, but LAED is much, much worse.

To quote Riana Pfefferkorn, Assoc. Director of Surveillance and Cybersecurity at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society:

“It’s Really Bad”

To expand on the above, a few lines later we have the following:

“The bill’s wording is unambiguous: providers, across the spectrum of devices and information services, must design in the ability to decrypt data and provide it in intelligible form. That applies to providers that have more than a million U.S. users. This applies to both stored data (whether locally on a device, or remotely) and data in motion (i.e., communications in transit).”

Source: There’s now an even worse anti-encryption bill than EARN IT.

I highly recommend reading that article, if those quotes piqued your interest.

So, let’s open this can of worms, what’s wrong with a backdoor?

Implementing a backdoor requires a fundamental redesign of how many basic encryption processes work, they’re designed explicitly to prevent 3rd parties from reading or altering any content.

But, let’s say, for the sake of argument, that we modify how our encrypted communications work, what happens when the very people we’re trying to catch with these measures gain access to those backdoors?

All it takes is one government agency being compromised, or someone poking around and finding the backdoor, and the flood gates are opened. Do we trust government security that much? By putting in these measures we would double the potential for leaks and hacks, since not only does the service have to secure itself, the government does as well.

A compromised universal backdoor into all communication would unleash mayhem. I think there’s nobody better to illustrate this concept than Tom Scott, he has a wonderful video where he goes over what would happen if everyone could access each other’s Gmail accounts. Imagine this but only malicious actors could gain access, and it wasn’t just Gmail.

Providing backdoors into common services would be a timebomb with absolutely catastrophic effects.

And, to top it off, it probably wouldn’t work anyway, since the good citizens of the world would no doubt move to government authorized backdoored platforms, leaving them vulnerable. However, malicious actors would continue to use encryption anyway. They’re already planning on breaking the law, why stop?

Splitting the Net

The US has, very recently, announced its plans to effectively block all Chinese traffic, ironically this would probably involve copying China and implementing a giant firewall to prevent “unlawful” content.

The repercussions from this act are hard to guess, but perhaps the worst is the precedent for controlling the Internet so heavily.

There’s already a collection of countries that heavily control what’s available to their citizens, such as Turkey, but the US doing it paves the way for countries such as Australia and the UK to expand their reach and follow suit.

For this to affect you, you don’t even need to be in the country that’s enforcing censorship, just nearby.

Subsea cables are everywhere, but they don’t often connect places directly, instead connecting via hops, where for your data to reach its destination, it passes through several peering points.

So, if one country blocks peering with another, then all traffic that would route through that country (eg: connecting to Sweden goes through Germany and Hong Kong). This means that one country controlling its traffic can have a flow on effect to its neigbouring countries.

Impact On the Rest of the World

With the US beginning to tighten its grip on technology, we may begin to see flow on effects, as legislators inside and outside of the US leverage the precedent to enforce their destructive views.

Further repercussions come from the US and China’s power, due to the combined size of their markets, if your app is removed from both (assuming you could penetrate China to begin with), you’ll very quickly lose a large portion of incoming revenue. This revenue loss could be crippling for small or growing startups, damaging an already volatile business.

Countries that care about Privacy, such as EU members, will have no choice but to cut contact with the US if these destructive cryptographic backdoors are implemented. Services that operate in both countries will be forced to segregate their platform, with one side controlled by strong privacy regulations and the other the complete opposite.

This level of control is disheartening, a once open platform ever converging to a censored, regulated, and divided forum.